- Beth Hoff

- Nov 18, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 1, 2022

If you had driven down Longmeadow Street around the turn of the 20th Century, you would have definitely noticed the Medlicott house at 720 Longmeadow Street. This imposing home caught the eye of Longmeadow photographer Pasiello Emerson and he photographed it many times.

While we refer to the building as the “Medlicott house”, Mr. Medlicott was not its first owner. Captain Calvin Burt, a merchant in Longmeadow, built the house around 1786 near the north end of the Longmeadow green. A contemporary of the Richard Salter Storrs house (now the Storrs House Museum), the Calvin Burt house was situated just north of what is now the Brewer-Young Mansion.

Capt. Burt passed away in 1848 and William G. Medlicott, a woolen stockinette manufacturer, purchased the house from the Burt estate in 1851.

William G. Medlicott courtesy of Stephen Forbes

Mr. Medlicott, his wife, and his five children lived in the Burt house and, by 1864, he had substantially remodeled the house. Last summer, a descendant of the Medlicott-Allen-Kibbe family shared a collection of family photographs with the Longmeadow Historical Society; included in the collection is an image of the Calvin Burt house before it was remodeled.

In addition to altering the façade of the building, William G. Medlicott substantially enlarged it. It is likely that Mr. Medlicott needed the extra space to hold his 20,000 volume private library. On the 1910 map of Longmeadow, the home looks comparable in size to its neighbor to the south, the Brewer-Young Mansion. The map shows a barn behind the house, and there was also a garden. The view from the back of the house stretched westward to the Connecticut River.

1910 Map of Longmeadow

William G. Medlicott died in 1883 and probate records show that he left all of his properties to his daughter, Mary.

Eliza Medlicott continued to live in the house with her daughters Mary and Bertha until she died in 1907. Son William B. and his family moved back to the Medlicott house after his mother’s death and they lived there with Bertha and Mary until William B. and his family moved to Cambridge. In 1916, Bertha moved to Northampton and Mary moved to Springfield.

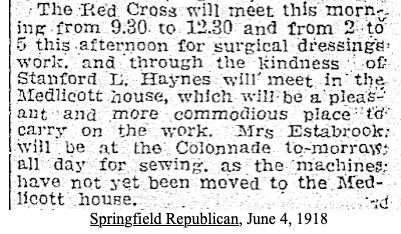

In 1917, Stanford L. Haynes, the neighbor who lived just north of the Medlicott house, purchased the house and, in 1918 and 1919, it became the headquarters of the Longmeadow chapter of the Red Cross.

Stanford L. Haynes died shortly afterwards and, according to a 1921 article from the archives of the Longmeadow Historical Society, his estate sold the Medlicott house, but not the property, to Charles N. Dunn, president of Bay State Storage and Warehouse Company. Mr. Dunn planned to use elements of the house in his “fine new residence” on Sunset Road, overlooking the river, at the south end of Longmeadow. Unfortunately, Mr. Dunn subsequently had financial difficulties and I can find no record that he ever built his new home.

1921 newspaper article

The Medlicott house was torn down and it disappeared from Longmeadow over 100 years ago, but we are fortunate that we have so many images which document the grandeur that it once represented.

Sources

Special thanks to Stephen Forbes and James Moran

Longmeadow Historical Society archives

Hall, J. R. 1990. William G. Medlicott (1816-1883): An American book collector and his collection. Harvard Library Bulletin 1 (1), Spring 1990: 13-46. William G. Medlicott (1816-1883): An American book collector and his collection (harvard.edu)

Springfield Republican, June 4, 1918

"Use Materials in Old House," 1921 newspaper article

“Miss Medlicott, Librarian, Dies at Age of 81,” Springfield Republican, March 3, 1927

Massachusetts, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991

1831 Map of Longmeadow

1910 Map of Longmeadow

Contributed by Elizabeth Hoff, Longmeadow Historical Society Board Member

Originally published March 10, 2022